This is Chapter 18 of How to Dismantle an Empire. It ends Section FIVE: Lands of Milk and Money, which is on system change. This chapter imagines a global network of small scale sovereignty, and what would be possible. It compares Afghanistan to Switzerland, the Maoists of India to the Zapatistas of Chiapas, and an African girl to a British pound.

We have two countries here under one flag, one constitution and one language. One part of Brazil is in the twentieth century, with high-technology computers and satellite launches. And, beside that, we have another country where people are eating lizards to survive. —WILSON BRAGA, 1985 Most days I wish I was a British pound coin instead of an African girl. Everyone would be pleased to see me coming. ... A pound coin can go wherever it thinks it will be safest. It can cross deserts and oceans and leave the sound of gunfire and the bitter smell of burning thatch behind. ... A girl like me gets stopped at immigration, but a pound can leap the turnstiles, and dodge the tackles of those big men with uniform caps, and jump straight into a waiting airport taxi. Where to, sir? Western Civilization, my good man, and make it snappy. —CHRIS CLEAVE, LITTLE BEE This is a book not about the decline of America but rather about the rise of everyone else. —FAREED ZAKARIA, THE POST-AMERICAN WORLD

Chapter 18: World Without Ends

While globalization promised to erase borders, the effect has been the opposite: a seismic shift of the ground beneath the rich and the poor, widening the gap between them into an impassible chasm. Within single countries are obscene extremes, as Albert Camus said of Brazil: “I have never seen luxury and misery so insolently mixed.” In attempts to cross the perilous divide between rich and poor countries, migrants and refugees perish daily or succeed only to win a life of servitude and fear.

But borders exist only in the minds and actions of their beholders. As a concept, they have no more tangible reality than money and, like money, are verbs describing an action rather than nouns describing things. Their strength lies in their power to maintain a different set of rules for people on either side of an arbitrary line. The purpose of a border is to separate slaveowners from slaves so that populations can be subjugated as a whole and slaveowner rights can become a matter of national security.

Once a line has been drawn in the sand, or the dirt as the case may be, to rebel against the rules—or against who gets to make them— is insurgency no matter how many people agree on the new identity. A border can protect a community’s power over itself or an empire’s power over others. If a community isn’t allowed to decide for itself where its border ends and what functions it includes, they are the colonial possession of an empire.

A modern movement has been turning away from consolidation and towards smaller republics. Let’s look at how the world would look if the right to control its own economy was automatically available to any population of a particular size, irrespective of its historical alliance or the name by which it was known. Instead, we'll apply the terms from the last chapter of commonwealth for hundreds of thousands, EcoStates for millions, federations for tens of millions, and trade blocs for hundreds of millions of people.

the antidote to civilization

The governments with the largest sets of people are India and China, each with over a billion people and over four times the size of the next-largest country, the United States. The People’s Republic of China is a single-party state with jurisdiction over 1.35 billion people in 22 provinces, five autonomous regions, four direct-controlled municipalities, and the "special administrative regions" of Hong Kong and Macau.

Hong Kong’s peaceful return to Chinese rule in 1997 was seen as ending China’s “century of humiliation.” But in the seventeen years since, China’s policy of “one country, two systems” has proven to be just another slogan. Candidates for Hong Kong’s presidential election are selected by Beijing for their patriotism and loyalty. In 2003, when Beijing insisted that Hong Kong put prohibitions against treason and sedition into their constitution, 500,000 of Hong Kong’s seven million people went into the streets. But Hong Kong is big enough to be its own EcoState, controlling its own economy and protecting its ecosystem and the sovereignty of its own commonwealths.

Currently China is the world’s largest exporter and the third-largest importer of goods behind the US and the EU. However those who make the exports in China are not the same people who receive the imports. China has 482 million people living on less than $2 a day, most of whom are rural peasants who have been driven off the land and into provinces like Guangdong to live in locked barracks and work 14-hour days. The estimated four to five million child laborers in the economic zones could join as their own federation to protect worker rights. Instead, elementary school children have quotas to braid 1000-10,000 strands of firecrackers a day, which periodically blow up.

We might imagine China’s 1.35 billion population as three or four trading blocs, each with a dozen federations made up of a dozen EcoStates. Thinking of China in this way raises questions. How should the gambling and shipping nation of Macau, at 600,000 people, relate to the export-manufacturing federation of Guangdong, at 80 million residents plus 30 million immigrant workers? Does Macau’s gambling hub siphon money away from local economies or bring money into them? Who should regulate access to ports? If China became a number of federations, each controlling their own land distribution policies, would people still migrate away to work in factories or would they return to being farmers? And will there be workers for the sweatshops now that the generation of the one precious child are all grown up?

walking with the naxalites

Going in the opposite direction, with a population growth rate of 1.1% per year, are India’s 1.3 billion people, one-third of whom are under sixteen. India is divided into 36 states and 678 districts. The Naxalites, also known as the Maoists, are active in 180 districts in ten states. The prime minister has called them “the single biggest internal security challenge ever faced by our country,” and later told Parliament that “if Left Wing extremism continues to flourish in important parts of our country which have tremendous natural resources of minerals and other precious things, that will certainly affect the climate for investment.”

However, a Planning Commission report on the Maoist movement admitted that, “Though its professed long-term ideology is capturing state power by force, in its day-to-day manifestations, it is to be looked upon as basically a fight for social justice, equality, protection, security and local development.” Arundhati Roy’s book, Walking With the Comrades, portrays them likewise to be a militant peasant force focused on issues of food and local sovereignty:

... the Maoists’ guerrilla army is made up almost entirely of desperately poor tribal people living in conditions of such chronic hunger that it verges on famine of the kind we only associate with sub-Saharan Africa. They are people who, even after sixty years of India’s so-called Independence, have not had access to education, health care or legal redress. They are people who have been mercilessly exploited for decades, consistently cheated by small businessmen and moneylenders, the women raped as a matter of right by police and forest department personnel. Their journey back to a semblance of dignity is due in large part to the Maoist cadre who have lived and worked and fought by their side for decades.

If communities’ right to control their own land were universally recognized, they would be considered a public militia for self-defense, not terrorist guerillas. Operation Green Hunt is a government military program whose CEO’s professed goal is to get 85% of India’s people off their land and into the cities. It protects the memorandums of understanding (MoU's) that have been written with mining companies for the ores hidden under the land that’s inconveniently occupied by peasants. Their strategies include arming paramilitaries that commit unconscionable atrocities and burning villages to flush the Maoists out, creating hundreds of thousands of refugees.

If the district government—whose departments collect revenue, police the villages, and manage the forests—worked for the community rather than a distant bureaucracy, none of this could be happening. The Maoists would be farmers who had the right to bear arms in self-defense.

the bourgeois democracies of southeast asia

The next-largest population after the US is Indonesia with 255 million people. In a trade bloc made up of Southeast Asia, it alone would encompass three or more federations. The Philippines and Vietnam, each with over ninety million people, would be large federations on their own. Is it strange to think that, in a world where people count equally, the Philippines would have twice as much clout as the Pacific Coast of the United States? Or that the whole northeast US, with its knobby backbone of densely-populated cities, is smaller in population than Vietnam? Walden Bello of Foreign Policy in Focus was deeply involved with land reform in the Philippines after the 1986 ouster of dictator Ferdinand Marcos. He found that:

Even more than dictatorships, Western-style democracies are, we are forced to conclude, the natural system of governance of neoliberal capitalism, for they promote rather than restrain the savage forces of capital accumulation that lead to ever greater levels of inequality and poverty. In fact, liberal democratic systems are ideal for the economic elites, for they are programmed with periodic electoral exercises that promote the illusion of equality, thus granting the system an aura of legitimacy.

He might apply the old Marxist term “bourgeois democracy” to describe this kind of government that combines imperialism abroad with elections at home.

In an article titled, “How Liberal Democracy Promotes Inequality,” Bello finds that his generation’s work to oust dictators in Chile, Brazil, South Korea, and the Philippines didn’t result in greater land distribution and self-sufficiency. Using the Philippines as an example, he demonstrates how the elites give a show of electoral competition while consolidating economic power as a class. He writes:

Ultimately it was not a dictatorship but a democratically elected Congress that passed the automatic appropriations law that allowed foreign creditors to have the first cut of the Philippine budget. It was not a dictatorship but a democratically elected government that brought down Philippine tariffs to less than 5 percent, thus wiping out most of our manufacturing capacity. It was not a dictatorship but a democratically elected leadership that brought us into the World Trade Organization, opening our agricultural market to the unrestrained entry of foreign commodities and leading to an erosion of food security.

Today, even as the elites battle it out in the Philippines’ thriving electoral politics, the rate of poverty—at nearly 28 percent— remains unchanged from the early 1990s.

What Bello shows is that it’s not the form of government that matters, but the size at which sovereignty can be exercised. Perhaps peasants understand the link between foreign debt or tariffs and food security better than academics. If we were to become masters of unlearning, we might reach the clarity of a Peruvian tenant-farmer in the high desert growing asparagus that ships to the US. Then we would replace the idiocy of the free market with wisdom rather than rationalization.

home bases in a thousand places

The 34 US military bases on Okinawa are another demonstration of lost sovereignty. During the US wars on Korea and Vietnam, Okinawa was used to stage bombing missions, thwarting peaceful relations with their neighbors. Due to the military impunity granted to servicemen, sexual assaults happen with frequency, including the kidnapping, rape, and murder of a five-year-old girl. In addition, chemical and biological weapons have leaked or been field-tested there, endangering the rice crop and the water supply.

Okinawa has been a sacrifice zone for Japan since it was annexed in the 1870s. To spare the mainland in WWII, Japan localized the violence to the island so that as many as a third of Okinawans died in the Battle of Okinawa. After the war Japan signed a peace treaty but left Okinawa under US military rule. Bulldozers razed houses and survivors were expelled at gunpoint to make way for military outposts. Today a new base is being erected at Henoko—despite a mayor elected on an anti-base platform, a poll showing that 80% of residents oppose it, and thousands of protesters staging flotillas, marches, and sit-ins.

If the US were a trading bloc rather than a centralized government, would it be able to fund 1000 military bases around the world—an average of five per foreign country? Why would any other federation allow such an imposition? With relative equality of size and the freedom to associate with like-minded others, expansion and domination would be impeded and the UN Security Council, NATO, the G7, the IMF, the BIS, the WTO, and the WEF would have no purpose.

At 1.4 million people, the island of Okinawa could make up its own EcoState with the mandate of protecting its natural resources. It would have neither the ability to sign away the land rights of a commonwealth like Henoko nor to send in police to suppress resistance. Henoko would be able to align with other peaceful and environmentally minded commonwealths and EcoStates. Perhaps they would partner with peace-loving Japanese to bring back the golden age of the Edo Federation.

a mosaic of economies

During the Edo period from 1603 until 1868, Japan was a flowering of small-scale sovereignty. Azby Brown lived in Japan for three decades and authored several books about the genius of compact yet elegant Japanese architecture. His article for the Global Oneness Project, entitled “Living with Just Enough,” describes how Japan faced deforestation and dwindling resources, shortages, and famine. But then:

... after two or three generations of wise regeneration, the large population was enjoying a quality of life arguably higher than in any contemporary European country. The forests had been saved, agricultural production had increased manyfold, and culture and literacy were on the rise.

He describes how a decentralized economy enabled this resurgence:

Intriguingly, government policy was most effective when the goals and principles were laid out by the central bureaucracy and each region was encouraged to develop local solutions. In many ways, this local thinking and responsibility lay at the heart of the success of the program to achieve self-sufficiency and sustainability on a national scale. Though a very active national trade network existed, each of the dozens of fiefdoms into which the country was divided was encouraged to be as self-sufficient as possible. Each village in a fief was encouraged to do the same, as was each family in a village.

The result was what we might call a "mosaic of economies," in which government and trades people were the most dependent on the cash sector, while villagers could meet most of their needs without every touching money, utilizing a "gift economy" in which surplus goods were circulated as reciprocal gifts until every household had pretty much what it needed. Ironically, most low-ranking samurai, whose fixed incomes—paid in rice— failed to keep pace with inflation, found themselves increasingly dependent on the same "gift economy" system.

Unable to buy enough to eat, little by little they converted their urban pleasure gardens into vegetable plots, and, forbidden from selling their produce on the market, secured what they needed by circulating their surplus through a network that included their neighbors and relatives.

Brown suggests that, from this necessity to heal the environment and be resource-thrifty, they developed an aesthetic that valued the hand-made and combined clean and vibrant form with useful function. If few items were possessed, the ones they owned had to be durable, repairable, and appealing to the eye. Even food was artfully presented in the miniature arrangements we call sushi, celebrating bits of seafood with beautiful frames of seaweed and rice.

eurusasia

If Japan was finding satisfaction with less during the 18th to mid-19th centuries, the European empires were all about acquiring more. By 1922 the British Empire ruled over 458 million people or one-fifth of the planet’s then-population; now the United Kingdom has 63 million people. If Scotland’s five million ride away on unicorns, three million Welsh march off playing hornpipes, and two million Northern Irish return to the Republic from whence they came, it would leave the Untied Kingdom with 53 million people—one reasonably sized federation.

Even Europe’s claim to be a continent has the mark of hubris for a peninsula with only four-percent of the world’s landmass. In a prime example of politics trumping geography, the arbitrary border between Europe and Asia cuts right through Russia, giving Europe 75% of Russia’s people and Asia 75% of Russia’s land. Dictionaries fumble to define the word continent because “a large, contiguous land mass mostly surrounded by ocean” leaves out Europe. Wikipedia writes,

Some view separation of Eurasia into Europe and Asia as a residue of Eurocentrism. 'In physical, cultural and historical diversity, China and India are comparable to the entire European landmass, not to a single European country. A better (if still imperfect) analogy would compare France, not to India as a whole, but to a single Indian state, such as Uttar Pradesh.'

In fact, Uttar Pradesh’s 200 million people triples France’s 66 million. The Russian Federation is a better comparison with 144 million people divided into 83 “federal subjects”, although the term ‘subjects’ belies federalism because it denies their sovereignty and implies that they serve the federation rather than the federation serving them. Russia encompasses nine time zones within one expansive country, and could be a trading bloc on its own.

Without Russia, all of Europe has fewer than 600 million people, which is half the size of India. They could embody one trading bloc with a dozen federations made up of EcoStates and commonwealths. The austerity-imposing countries—Germany, France, and the UK, with a combined 250 million people—could each be their own federation and leave the others to their own devices. Perhaps true federalism is the antidote to economic imperialism.

swiss knives and afghan quilts

True federalism seems to have less to do with the style of government and more with size. According to Johan Galtung—the founder of Peace and Conflict Studies, who negotiates between the Taliban and the US—Afghanistan and Switzerland have more in common than you might think. In a Democracy Now interview, he advised that:

You have to understand what kind of country Afghanistan is. As Taliban tell me, it’s a very, very decentralized country—25,000 very autonomous villages, and let us say six to eight nations, depends on how you count it. And I remember when we in Transcend, an NGO for mediation, had our first effort there in February 2001, long before 9/11. Then, I was asking myself, "What country does this remind me of?" which I always do when I mediate. And the answer was Switzerland. Switzerland is the model. Switzerland is a very federal country with very high autonomy down at the local community. Let us say they have 5,000, not 25,000; they have four nations, not six or eight. And Swiss policy is to be neutral, non-aligned, and to be a very, very deep federation.

I think Afghanistan’s future will be heading in that direction. ... they hate Kabul as an overblown, over-bloated kind of capital carrying the illusion of a unitary state. It isn’t. And I think that they would prefer to see a very small center of the country and very high level of autonomy. In addition, they are sick and tired of being invaded. It started with Alexander the Great. You know, this is the place where he became Alexander the Small. And they were invaded by the Mongols, three times by the Britons, one time by the Soviets, and now by the U.S.-led coalition, as you said, NATO forces. So, for them, this is also a war to fight being invaded, the war to end wars.

The Swiss Confederation, which is the full name of Switzerland, is comprised of 26 cantons for 8 million people, which comes to about 300,000 people each. But, as Galtung indicates, these are further divided into an average of 200 local communities each comprised of around 1600 people. Although they don't have a common language, their unity is based on the shared values of disarmed neutrality, federalism, and direct democracy. Decentralization has kept Switzerland out of armed conflict and made Afghanistan an impenetrable maze for invading empires. Few unified nations can say the same.

bolivia, the plurinational

On another continent, the indigenous president of Bolivia, Evo Morales, has recognized that the Bolivian state of 10.5 million people contains many autonomous nations and has popularized the term plurinational. The state is divided into nine departments, which are comprised of 112 provinces sectioned into 339 municipalities, cantons, and native community lands. Averaged out, there would be 93,000 people per province divided into three cantons of 31,000 each.

However, in practice, plurinationalism is not working as well as in theory. The World Bank and IMF have never been happier with Bolivia now that a charismatic native leader has quadrupled the area open to gas extraction—twelve million hectares with over half ceded to multinationals—while steamrolling over regional sovereignty. There has also been an acceleration of mineral mining and agro-monocultures, mostly in soy production, and a highway project is plowing through both tribal land and a national park, with more development sure to follow.

To be fair to Morales, however, any elected head of a resource-rich country is in a bind. Given an implicit choice, most people will prefer to consume more than they produce. This standard of living is only made possible in two ways: selling the natural resources of internal colonies or using foreign militarism to dominate and exploit external colonies. While State and World Bank officials point to Bolivia’s rising GDP and narrowing income disparity, the cost of food is also rising, which affects the poor disproportionately, creating more dependence on money. Meanwhile Bolivia’s treasury is accumulating a surplus, which it sprinkles into social programs, buying off the opposition and repressing protest when that fails.

But charity is not sovereignty and a hand-out doesn’t replace social justice. If Bolivia were apportioned ethnically, there are roughly 2.5 million Quechuans, 2 million Aymaras, and 3 million mestizos. This is enough to each have their own EcoState, with another comprised of Euro-Americans (including the German-speaking Mennonites) and other ethnic nations like the Guaranies and AfroBolivians. If one EcoState failed to keep its charter to protect its natural resources, its commonwealths would be free to join another. Then, if those in urban areas wanted to consume without producing, they would have only their own natural resources or labor to sell.

a hand-out or hands-up

The sole function of an EcoState is to protect the natural resources shared by the commonwealths under its alliance. The smaller the community, the less their ability to outsource the real costs such as the arsenic in Chiapas's water from gold-mining or the destruction of the mountains of India from bauxite-mining. When one centralized government makes decisions for remote regions, they become internal colonies.

The United Mexican States, as a federation of 120 million people, has been one such government that controls rather than negotiates between its 31 entities. In 1900 the population was only 13 million; the nearly ten-fold increase has resulted in nearly half being under 25 years old. While the birth rate has dropped from 5.7 per woman to 2.2 in recent decades, the boom created an urban migration. One-fifth of Mexicans now live in the metropolitan area of Mexico City and three-fifths live in other cities, leaving only 21 million who are rural. Mexican policies had disregarded this minority who live off the land.

But the countryside fought back. On the day that NAFTA went into effect, January 1, 1994, a peasant army declared war on the Mexican government, seized major cities in the state, burned down the army barracks, and freed the prisoners. Today in the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas, over one thousand Zapatista communities-in-resistance have joined together in 38 autonomous regions. The Zapatistas have just celebrated 20 years of masked militancy, guarding the people from attack by paramilitary troops.

Today in the five Zapatista caracoles, as the regional centers are called, government hand-outs are banned as bribes to create dependency, health clinics mix traditional cures with allopathic medicine, and the school curriculum is set by community and taught in the indigenous language. A recent addition to the caracoles is la escualita or the little school, where 4000 foreign students have come to be paired with tutors and placed in host homes to learn “freedom according to the Zapatistas.”

With a population of 3.4 million people, Chiapas is a working model of an EcoState where local identity and horizontal organizing are being explored. Perhaps, with the new government in Mexico, it might be truly “Free and Sovereign” so their youth wouldn’t need to protect against Mexican troops and paramilitaries and could concentrate once again on farming.

may the federation be with you

A federation is based around an ideology. It might be neutrality and democracy, like Switzerland, or tribal independence like Afghanistan. It could be mutual aid in disasters, shared opportunities in higher education, or better coverage in healthcare. A federation’s goal could be to support farmers, at home and abroad, and prioritize their needs. Another federation might grow a generation of doctors, or artists, or teachers. Although each republic is responsible for itself, a federation could provide the neural network to communicate ideas.

There are no easy answers to these questions, but applying the golden rule to governments means that whatever rights and privileges would be claimed for one's own community must be recognized in its policies towards other social bodies. If governments were judged merely on their internal and external consistency, another world would be possible. Each commonwealth would be a republic of abolitionists who could buy their own freedom by freeing the slaves. Our EcoStates would protect our resources and collaborate to reverse climate change, if that’s their goal. Our federations would preserve the best of globalization so an African girl could jump the turnstiles more easily than a British pound, and money and weapons would stop at borders so that people could be free.

CHAPTER 18 EXERCISES

Using examples from the book, or from your own research, logic, and experience, comment on how the following changes the questions:

Paradigm Shift #18

There are only two human rights:

the right of community self-governance

and community ownership of land and resources.

Human rights are predicated on community rights.

LEXICON

Explain how the following definitions change the dialogue around social problems. Is this concept used in discussion of the examples to which it applies? If not, how does this affect the potential solutions?

borders: arbitrary locations where people are restricted from going in the same direction as the unrestricted flow of money and goods.

Naxalites or Maoists: sovereignty guerrillas of rural India who protect communities against State-sanctioned terrorism designed to drive them off their land and into cities.

Memorandums of Understanding (MoU's): signed contracts between governments and corporations giving them access to resources located in remote provinces, often inhabited by indigenous populations living off the land.

bourgeois democracy: Marx's term for an electoral system run by elites. It gives the consumer class voting rights but excludes the supply chain of producers as non-citizens.

decentralized economy: a centralized system that sets out the goals and principles but leaves each region to develop local solutions within a common set of parameters.

plurinational: one state that contains many autonomous nations with different cultures and ethnicities.

QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION AND DISCUSSION

Should secession be possible for groups of people who feel treated unfairly by their umbrella group or forced to act in ways they consider immoral, such as the funding of war or contraceptives, or the expelling or inclusion of immigrants? Could the rights of secession and voluntary association solve any conflicts that seem intractable?

Comment on Walden Bello's observation that Western-style liberal democracy promotes inequality and is the preferred method of governance by elites. Do you agree or disagree?

How should land disputes be settled? Is there a statute of limitations on land theft and does the right of reparations favor genocide, because few survivors are left? Should there be common armies, nuclear arsenals, or treaties for the common defense? Could the latter be triggered by false flag events, or escalate the mere killing of an Archduke into a World War? Is there an economic way to protect each others' sovereignty, such as trade embargoes and an interfederational court?

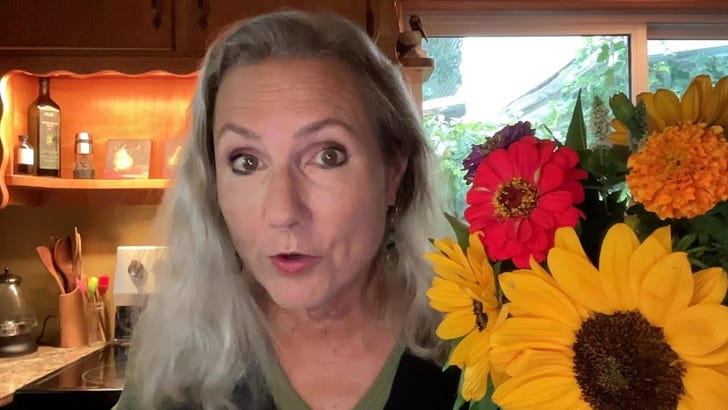

What I learned this week: Aaron Mate on US arming terrorists in Syria, Kanekoa on the Ukranian oligarch funding Hunter Biden, Zelensky & Azov, Moon of Alabama on Russia entering phase two, Scott Ritter on Russian strategy and false flags, Pepe Escobar interviewing Putin's economic czar, Sergey Glazyev on the new global financial system, and Vijay Prashad on "We Don't Want a Divided Planet; We Want a World Without Walls." I end with some hopeful ways in which the empire might be dismantling itself and preparing the ground for a network of small, local economies.

While we dance on the brink of nuclear war, NeoCons and ZioCons argue who we should provoke into annihilating the world. I look at geopolitics from Pepe Escobar, Fadi Lama, Chuck Baldwin, Cynthia Chung, Mike Renz and Oliver Boyd-Barrett.

18: World Without Ends

https://open.substack.com/pub/thirdparadigm/p/18-world-without-ends

TEREZA CORAGGIO 2025.08.15 Friday

https://substack.com/@thirdparadigm

I remeber the days when every country was pushed to join the World Trade Organisation what was rever a real international organisation but an arbitration mechanism in the fashion of anglosaxon maritime law im which the judges can be bribed. Another empty shield is the OECD. They actually worked to abolish international law which is now dead, as was intended. I think BRICs is a desperate move to rebirth a minimal standard of international law. But to have international law we must have nations in the first place, which is contrary to globalism and free capital movements for a world market, as Marx predicted before the end of capitalism by the take over of the working class. Globalism has lost momentum now as chaos has overcome over reliable rules. I think a global deal for minimal standards is in the oven but the west is reluctant to accept the end of its hegemony.