A recent article on Robert Malone’s Substack was titled What an Article 5 Convention might mean. He had been giving a speech to the John Birch Society and invited them to post an article on this topic on his site. He prefaced it with some history of the JBS and their positions on topics from free trade agreements to the Federal Reserve. While he doesn’t feel they’ve been right about everything, he suggests, in the interests of intellectual integrity, approaching what they have to say with an open mind.

As I posted in his comments, in high school I wrote a paper comparing the JBS and the Black Panthers, back in the early ‘70’s. Being the Dark Ages, I sent away for literature. What I found is that they were both for protectionist economics and armed self-defense but against military interventions abroad and social welfare systems at home (aka communism) and for self-governance at a local level. They had more in common than was different. Clearly, my contrarian roots run deep.

In my book, How to Dismantle an Empire, the Constitution takes up the better part of a chapter called ‘The Short Eventful Life of Sovereign Money.’ Let’s look at the instigation for it, starting with Ben Franklin’s scrip, on which I base my own economic model. At 23 he published an anonymous tract called “A Modest Inquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency.” When it turned public opinion in its favor, he landed the contract to print the currency, launching his career. However:

In 1763 the now mature Franklin was again called before the British Board of Trade. Prior to his appearance, he had occasion to travel throughout Europe where he was shocked by the poverty and desperation. He advised the Board that Europe, like Pennsylvania, could become a model of egalitarian prosperity where every man was a property owner, “has a Vote in public Affairs, lives in a tidy, warm House, has plenty of good Food and Fuel, with whole clothes from Head to Foot, the Manufacture perhaps of his own family.”

In Pennsylvania, he continued, there were no poorhouses, and no one to put in them because every willing person was employed. Rather than creating a social welfare state, the scrip empowered families and neighborhoods to take responsibility for themselves. The scrip also organized labor for the common good, enabling two of Franklin’s social inventions: the postal service and the free library.

This had the opposite effect on the Board from Franklin's intentions. Horrified by the implications, within the year the Virginia Company of London had pressured Parliament to outlaw all colonial scrips. The British Currency Act of 1764 forced the colonies to go back to gold and silver coins and specie. Their reserves were soon depleted, plunging them into foreclosures and economic depression. By 1771 the trade deficit with Britain had grown to £2.86 million. According to Franklin this was the real cause of “the American discontent,” not a trivial tax on tea or stamps. [55-56]

This ‘American discontent’ became the Revolutionary War:

In order to pay for soldiers and weapons, however, Congress and the States needed money. Alexander Hamilton negotiated loans from his employer Robert Morris, who was the leading financier of the Revolutionary War. Other loans were from France and Spain or war bonds redeemable only if the colonies won. But two-thirds of the funding was issued as fiat currency by the newly formed states (39%) or the Continental Congress (28%). The latter were known as Continentals and were bills declaring their exchange value in the Spanish milled coins that neither the Congress nor the individual States actually possessed.

The reach of the Continentals throughout the 13 colonies destroyed the accountability of locally issued scrip, making them more vulnerable to counterfeiting. This was used as a weapon of war by British-occupied New York where newspaper advertisements offered to supply any person going into the colonies with unlimited high-quality counterfeits for the price of the paper. By 1777 a Continental was worth a third of its stated value and by 1781 it took 167 Continentals to buy one silver dollar.

The hyperinflation was not just from counterfeiting or overprinting, however, but because the foreign loans were denominated in foreign currencies rather than the sovereign currency of the Continental. If France, for instance, had bought "Continental futures" by generating fiat francs to pay for French soldiers and military supplies, it would have protected the economies of both countries. After the war, France would have used the Continentals to buy American exports, supporting American veterans back on their farms. The import goods, sold on the French market, would have replenished the French treasury and strengthened the trade value of the franc. Instead, Congress was required to extract the repayment in specie from the very people who'd given up the most to win the war: the farmers and veterans. When, in 1795, the loan was assumed by a US banker, the money never benefited the French people but went straight to the European merchant-bankers who financed the French throne and may have been the instigation for the war.

By 1781, Robert Morris stepped into the newly created role of Superintendent of Finance. First he devalued the Continental and then extracted $2 million in specie from the States. Finally he suspended all pay to enlisted soldiers and officers, declaring that they would be paid when a peace treaty was signed. The Paris Treaty was signed in 1783 and ratified in 1784, but pay was not forthcoming. Meanwhile, veterans owed back taxes on their farms for the time they had been away fighting. Adding injury to injury, the bankers were rushing tax foreclosures through a complicit court and evicting families from the homes and farms for which they'd fought.

It would have made sense for the newly formed states to issue their own scrip to pay the soldiers. They would have collected some of it back in taxes and left the rest in circulation so that patriots could buy land and goods. If the National assessment had been proportional to property and exports, it would have broken up monopolies in the North and plantations in the South, rewarded veterans with land, and paid foreign backers in products of the land. This is what ex-soldiers in Massachusetts wanted, but this wasn't what happened.

In 1786 Western Massachusetts farmers and veterans, led by Daniel Shays and Luke Day, surrounded the court to stop tax foreclosures. They demanded that an issue of liberty money be created by the state to pay the back wages promised veterans. A militia was sent to disperse the rebellion, but the militia also consisted of farmers and veterans, who ended up joining the protest. The angry crowd grew to 800 militia and 1200 protesters before the frightened court finally adjourned without a single foreclosure.

Shaken to his core, Samuel Adams drew up the Riot Act, immediately suspending habeas corpus and proposing execution for rebellion. George Washington wrote, "Commotions of this sort, like snow-balls, gather strength as they roll, if there is no opposition in the way to divide and crumble them."

Shays and Day planned to keep the snowball rolling by raiding the federal armory. While they were gathering men, Governor Bowdoin and the Boston merchants put in £6000 of their own money to hire 3000 mercenary militiamen from counties in Eastern Massachusetts. On the day prior to the planned attack, Luke Day sent Shays a note postponing for 24 hours. Bowdoin’s men, however, intercepted the note. When Shays reached the armory, the forewarned militia easily defeated his solitary troops, having fortified the armory's defenses. …

Seeing the popularity of the resistance, the merchant-bankers in the Massachusetts legislature wasted no time in passing the Disqualification Act barring anyone who had participated in the rebellion from voting or running for office. Four thousand people signed confessions in exchange for amnesty, and the financiers were reimbursed for the expense of the mercenary militia. [57-59]

This led to the Annapolis meeting that put a Constitutional Convention on the calendar:

Later that year twelve commissioners were to join in Annapolis for a “Meeting to Remedy Defects in the Federal Government.” These were merchants and bankers representing five states, including James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. Although the committee’s official agenda was limited to trade and commerce, their report, drafted by Hamilton, named the date for a future convention in Philadelphia with a broader scope to address "the embarrassments which characterize the present State of our national affairs, foreign and domestic."

Hamilton had already drafted 2,300 words on this very subject in 1783 in a "Resolution Calling for a Convention to Amend the Articles of Confederation." Of his twelve essential defects and remedies, the first was that the power of the Federal Government was too limited, second that it involved too many people in deciding how big and well-funded the army and navy should be, and how they would be used—for which he proposed an executive branch separate from Congress. Third, a judicial branch should make sure the interests of foreign nations and their subjects couldn't be overruled by regulations of the states. Fourth and fifth, the Federal Government needed the power of general taxation, particularly for the military, and to decide how taxes from the states would be apportioned. Sixth, it insisted that Federal debts be backed by funds, meaning specie or precious metals, and not mere paper.

The seventh defect was that there was no standing military, for interior or exterior defence, but that states in peacetime determined their own militias. Eight and nine objected that the states set the taxes on their own imports and exports, and that the Federal Government could not enter into commerce treaties (with foreign or native nations) that violated those of the states. … Finally, the Federal Government must have the ability to pass national laws to aid and support the laws of foreign nations, so that its international reputation would not be sullied. [60]

What were the Articles of Confederation that Hamilton found so embarrassing as a fledgling empire? In What the Anti-Federalists Were FOR, Herbert Storing writes:

The principal characteristic of that ‘venerable fabrick’ was its federalism: the Articles of Confederation extablished a league of severeign and independent states whose representatives met in congress to deal with a limited range of common concerns in a system that relied heavily on voluntary cooperation. Federalism means that the states are primary, that they are equal, and that they possess the main weight of political power. [9]

Patrick Henry, the most eloquent of the ‘anti-Federalists’, thundered his objection:

What right have they to say, We, the People? My political curiousity, exclusive of my anxious solicitude for the public welfare, leads me to ask, who authorised them to speak the language of We, the People instead of We, the States? States are the characteristics, and the soul of a confederation. If the States be not the agents of this compact, it must be one great consolidated National Government of the people of all the States. [12]

The name ‘anti-Federalist’ is an early example of the Orwellian double-speak that’s become a rule of thumb these day, with everything named the opposite of what it means. The ‘anti-Federalists’ opposed the Constitution because it wasn’t federal but a top-down, centralized, consolidated government. The ‘Federalists’ were Centralists and their Constitution abolished the federal government and put a centralized government in its place.

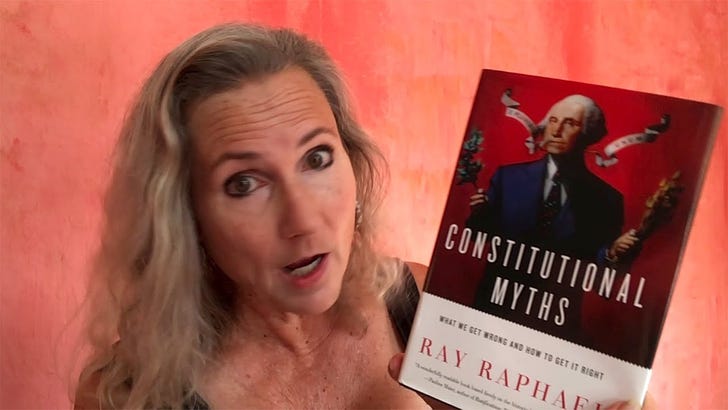

In Constitutional Myths, Ray Raphael states we have taxes to thank for the Constitution: “without the power to tax, the Confederation Congress was unable to deliver two of the most fundamental government services: protection of property and national defense.” But, as we saw with Shays’ Rebellion, those who had defended and even created the nation were having their property confiscated, not protected. So whose property did taxation protect?

These were the foreign merchants and bankers, speculators and financiers. The people wanted war bonds, for instance, to be redeemed for what speculators had paid, not their face value. “Such measures displeased the men we now call the founders. The net effect of debtor relief, they believed, was to deprive creditors of what was rightfully theirs, thereby nullifying the obligation of contracts.” This speaks to what David Graeber calls the “sacred nature of debt” that makes previously immoral and unconscienable acts into the norm.

The newly written Constitution still needed to be ratified by the States, which faced significant resistance, especially as an ‘up or down vote’ with no input from the people. When Massachusetts was locked, the Constitutionalists proposed that, if the opposing delegates ratified, they would work for the amendments they proposed to be included. That got them the needed votes.

The ‘Massachusetts Compromise,’ as it came to be called, persuaded the remaining States to ratify with their amendments. Virginia proposed twenty and a detailed ‘bill of rights’ of twenty more, North Carolina added six to these, New York proposed 32 plus 24 ‘principles’. They declared that the ratification wouldn’t be valid until a second convention had met.

It’s hard to tell which horrified the ‘founders’ more: the prospect of a second convention or the proposed amendments, with the most popular one prohibiting direct taxation unless States failed to meet their quotas. Madison figured out a solution—to write his own amendments that would be perfectly ‘innocent’ aka ineffectual. He privately called this his '“nauseous project of amendments.”

Washington wrote that while “not very essential, [they] are necessary to quiet the fears of some respectable characters and well-meaning men.” None addressed the structural revisions the States had called for. As one delegate said, without changing the power to tax, the people would value all the rest as no more “than a pinch of snuff.” A senator called them “milk-and-water amendments” and a waste of time that would do “neither good nor harm.”

Another Senator complained that “the English language has been carefully culled to find words feeble in their nature or doubtful in their meaning” resulting in amendments that were “much mutilated and enfeebled.” Patrick Henry said the missing amendment limiting direct taxation was worth more than all the rest put together. Another said they were “so mutilated & gutted that in fact they are good for nothing, & I believe as many others do that they will do more harm than benefit.”

When people praise the Constitution, they usually mean the Bill of Rights. But those who had written and hammered out the real amendments in their State Conventions knew it was a toothless, impotent placebo.

And what about Article 5 that gave the power to amend anything but Article 9, parts 1 and 4 before 1808. What was Article 9? It forbid Congress from making illegal the importation of people, aka slavery. It also counted 5 slaves as 3 freemen for representation, and set a tax at no more than $10 per head. The movement to abolish slavery was so strong that the Constitution needed to specify it as the sole article that couldn’t be amended. As NY Judge Robert Yates wrote anonymously as Brutus:

What adds to the evil is that these states are to be permitted to continue the inhuman traffic of importing slaves until the year 1808—and for every cargo of these unhappy people, which unfeeling, unprincipled, barbarous and avaricious wretches may tear from their country, friends and tender connections and bring into those states, they are to be rewarded by having an increase of members in the general assembly.

So the third priority for the Consitution, after direct taxation and a standing army in peacetime, was the protection of slavery. And as we know, 1808 came and went with more representatives of slave states in Congress and more dependence on the taxes they brought in. In fact the need for direct taxation to raise an army wasn’t needed until the Civil War—which could have been averted if the Constitution hadn’t tied the people’s hands.

Since we’re really talking about populism, a related video is Thomas Frank Misses the Point of Populism:

In Russell Brand's interview of Thomas, he quotes Steve Bannon that populism is the future, the only question is whether it's right- or left-wing. Thomas retorts that there is no right-wing populism, only left. I answer that if it's right OR left, it's not populism. In recent politics, I use the example of Ron Paul as more populist than Bernie Sanders. In the history of populism, I look at The Nonpartisan League in a book called Insurgent Democracy by Michael Lansing and how bipartisan politics gave money creation to the banks in Ellen Brown's Web of Debt. I end with the hope that we emulate the farmer Grange movement and come to agreement on policies that we support instead of parties.

and this is Debunking Democracy on Shoshana Zuboff:

Shoshana is the author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism and has been called the Karl Marx of our era. In Russell Brand's Under the Skin interview, she debates whether "a spiritual solution under autocracy is a fringe thing, full of despair that can't be realized", and only democracy can save us. Russell states that incremental reformism is an insipid milksop inoculating against real change. I explain why Russell is right and Shoshana is wrong, along with looking at the politics of narcissism and what a Marxism for our era would look like.

I’ve just come across your Substack and am enjoying it immensely. I’ve bought your book, but haven’t yet had a chance to read it. I’m not sure if this is the place to post this, but I am looking for some feed back. 2 friends and I came up with this concept for local currency based on art and advertising.

STEAL THIS IDEA!…PLEASE.

ART WORKS for COMMUNITY CURRENCY

K-TAW = Kindly-Tizing ArtWork :: a kind of funny money

ArtWork backed by community spirit of exchange

MISSION: We are artists banded together in partnership with businesses and community to exchange Art-Works in support of the local economy.

METHOD: Beyond permaculture currency. Barter. Banter. Build.

De-centralized. Organically local. Open Source. Bank on yourself.

PURPOSE: Dollar-sized ArtWorks used as advertising and gifted into the local economy. To be used by businesses and citizenry … to trade.

CONSUMER Instructions

1. Use ArtWork as you would cash for dinner, coffee, soda, tips, a massage, health care, child care, & more. Ask the community business if they take the ArtWork.

2. You may receive ArtWork in your change when buying a product locally, as a gift for a birthday, as a tip for a job well done, & more.

3. Closer to the expiration date (find date on the ArtWork), turn it back to the owner of the ArtWork and they will give you cash or more-than-equivalent services or products.

4. The more ArtWork is passed for exchange in the community before it is turned in, the more sustainable the community economy!

Get real…. Spend ArtWork…. Go local.

___________________

OWNER::BUSINESS instructions

Why use ArtWork as local exchange in Advertising:

--Get people talking about what you are doing.

--Use your advertising budget locally.

--Subtract the cost of your ArtWork as advertising.

--Watch people smile & laugh when “playing” with your “funny money”.

How to get started:

--Pay a small amount to a local artist for the ArtWork. Or make your own.

--Set aside an amount of cash to pay the “reward” for the return of the ArtWork. (You also may barter for the ArtWork with services or product.)

--Write or pay a writer to add:

1. Your business & slogan & offerings.

2. Your area of “good within ___miles of your place of business”.

3. Expiration date. Usually 3-6 months.

--Give your ArtWorks away.

1. You can only spend ArtWork other than your own.

2. Offer as a thank you to: Regulars, High pay customers, Bonuses &

Perks, Friends & Family, Lovers.

When the ArtWork is presented back to you

--Give cash or

--Give services or

--Give a product.

Keep gifting it out until closer to the expiration date.

_____________________

ARTIST instructions

1. You may

--Make your own ArtWork to advertise you and your business. OR

--Be commissioned to make ArtWork for someone else to advertise.

--Do one or the other because the Kindly-Tizing ArtWork is Open Source, meaning the ArtWork is not copyrighted. K-TAW believes in a gift society and a healthy local economy.

2. If you are commissioned to produce an ArtWork for someone else:

--You may sell your labor and supplies. Once a business, person, or a not-for-profit owns the ArtWork then the ArtWork totally belongs to them. They must set aside the “reward money” to exchange by the expiration date.

3. If you create the ArtWork for yourself to advertise yourself:

--You are the owner. When you own the ArtWork, you are the one who must set aside the “reward money” to exchange by the expiration date. The Owner must give ArtWork away as a gift to the community economy.

--You may take the cost of ArtWork off your income for advertising.

4. The Owner of the ArtWork must give/gift it away during the time period.

--Because if you sell the ArtWork, you

1. must pay taxes on the sale and

2. cannot deduct ArtWork as advertising.

5. ALL THE POINTS FOR THE BUSINESS OWNER APPLIES.

Thanks, much to process here.