People, I am in love. His name is Kandiaronk, which translates to ‘muskrat’ or Le Rat, as he was called by the French. In 1703, a soldier named Lahontan published four conversations with him called Curious Dialogues with a Savage of Good Sense Who Has Traveled. In them, Kandiaronk gives his views of Montreal, New York and Paris. He describes himself as a rational skeptic of Christianity, and gives an indigenous critique of European politics, health and sexual life. The book made Lahontan a celebrity and made Kandiaronk’s ideas widespread and influential in Europe during the period called the Enlightenment.

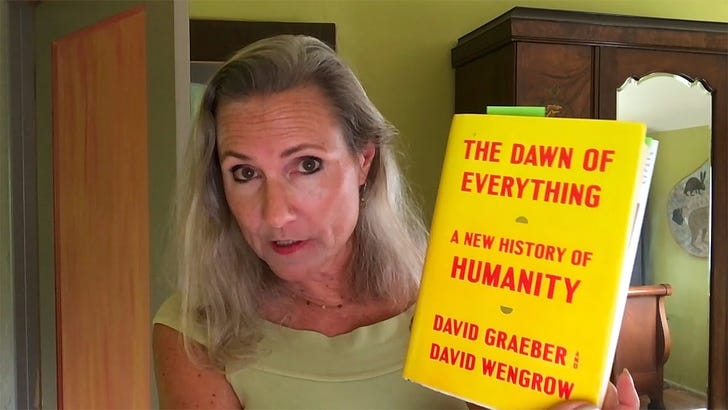

The late anthropologist David Graeber and archeologist David Wengrow write about him in their book, The Dawn of Everything. Graeber’s first tome, Debt: the First 5000 Years, changed how I thought about money and was the foundation for my book, How to Dismantle an Empire. In this book, they look at the freedom and creativity that people have brought to inventing and reinventing new social structures throughout pre-history, before written records. They give evidence that women were vitally involved in leadership, and that the rate of innovation paralleled the involvement of women. They outline three essential freedoms that all people took for granted before what we call civilization put a stop to that. And they end by asking how we stopped believing we could create our own social systems. They write:

The ultimate question of human history, as we’ll see, is not our equal access to material resources (land, calories, means of production), much though these things are obviously important, but our equal capacity to contribute to decisions about how to live together. …

We are projects of collective self-creation. What if we approached human history that way? What if we treat people, from the beginning, as imaginative, intelligent, playful creatures who deserve to be understood as such? What if, instead of telling a story about how our species fell from some idyllic state of equality, we ask how we came to be trapped in such tight conceptual shackles that we can no longer even imagine the possibility of reinventing ourselves? [8-9]

The idyllic state of grace goes back to Rousseau’s argument that people can only live peacefully in tiny bands of 10-12, maybe networked into Dunbar’s magic number of 150. Jared Diamond, who I just learned has his PhD in the physiology of the gall bladder, wrote about this in The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies?:

Large populations can’t function without leaders who make the decisions, executives who carry out the decisions, and bureaucrats who administer the decisions and laws. Alas for all of you readers who are anarchists and dream of living without any state government, those are the reasons why your dream is unrealistic: you’ll have to find some tiny band or tribe willing to accept you, where no one is a stranger, and where kings, presidents, and bureaucrats are unnecessary. [11]

The Davids show that the reverse is true: societies had leaders who sometimes exercised great arbitrary power, but without the mechanism of enforcement through executive layers and administrators, their reach was only in their immediate vicinity—which people tended to avoid.

Another person who saw civilization as saving us from ourselves is Steven Pinker, author of The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. In my episode Sex & Power: Battle of the Daves, I talk about Graeber and Wengrow’s critique of Pinker and how he cherry-picks a tribe to exemplify the violence he sees in human nature: the Yanomami or Fierce People.

But Chris Hedges, the Eeyore of sanctimonious political analysis, does the same thing in a recent article called The Final Collapse. He visits the site of Cahokia, a grain state near what’s now St. Louis, that existed from 1050 to 1350 CE and peaked at around 15,000 people or 40,000 including the satellite towns. Hedges admonishes:

This great city, perhaps the greatest in North America at the time, rose, flourished, fell into decline and was ultimately abandoned. Civilizations die in familiar patterns. They exhaust natural resources. They spawn parasitic elites who plunder and loot the institutions and systems that make a complex society possible. They engage in futile and self-defeating wars. And then the rot sets in.

The great urban centers die first, falling into irreversible decay. Central authority unravels. Artistic expression and intellectual inquiry are replaced by a new dark age, the triumph of tawdry spectacle and the celebration of crowd-pleasing imbecility.

Hedges compares Cahokia to St. Louis and the world today, quoting Jared Diamond from Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed:

Just as in the past, countries that are environmentally stressed, overpopulated, or both, become at risk of getting politically stressed, and of their governments collapsing … When people are desperate, undernourished and without hope, they blame their governments, which they see as responsible for or unable to solve their problems. They try to emigrate at any cost. They fight each other over land. They kill each other. They start civil wars. They figure that they have nothing to lose, so they become terrorists, or they support or tolerate terrorism.

The Daves also write at length about Cahokia which shares with Egypt the burial of kings with thousands of human victims, which archeologists treat as “one of the more reliable indications that a process of ‘state formation’ was indeed under way.” [399] But they found that:

Whatever Cahokia represented in the eyes of those under its sway, it seems to have ended up being overwhelmingly and resoundingly rejected by the vast majority of its people. For centuries after its demise the site where the city once stood, and hundreds of miles of river valleys around it, lay entirely devoid of human habitation: a ‘vacant quarter’ … a place of ruins and bitter memories. [452]

How did it end? The people defected and walked away. What replaced it were “polis-sized tribal republics, in careful ecological balance with their natural environment.” This brings up what the Daves see as the three essential freedoms:

to move away

to disobey

to build new social worlds

The Daves see the first two freedoms as a scaffolding for the third but they also show how the phrase “to move to a new country” was synonymous with constitutional change without necessarily leaving home. By the 1700s, petty kingdoms and pyramids had been entirely replaced by small towns with “egalitarian clan structures and communal council houses.” [471] Women took on leadership roles. In the Osage, the Nohozhinga or Little Old Men, which included women, would be sent off to deliberate on nature and philosophy as it related to political issues. Yet what was common to all the cultures was that they were decidedly anti-authoritarian, as a barrier against Cahokia, which was erased from the oral history.

The lesson reached by Hedges is that “The more insurmountable the crisis becomes, the more we, like our prehistoric ancestors, will retreat into self-defeating responses, violence, magical thinking and denial.” But that wasn’t what happened. They ‘moved to a new country,’ not by fighting the old system but by disregarding it and building something new. As the Daves say, these freedoms are taken for granted by anyone who has not been specifically trained into obedience, as anyone reading their book has been.

To put this together with Graeber’s book Debt, I think that money has enforced 3500 years of obedience training and that the term ‘blind obedience’ has it backwards. Money, as is shown in Debt and my book, puts us between a rock and a hard place. It forces us to do things to protect our loved ones that also cause harm to others outside our sphere. The invention of coinage and taxation required peasants to provide the material support of food, shelter, armor, sex to the lord’s army, who paid in the coin of the realm on their way to conquering their neighbors. Those coins enabled the peasants to pay the tax to keep their own families from becoming slaves.

When people do something against their conscience but see no other choice, they stop seeing it at all. It creates cognitive dissonance between “I am a good person” and “I enable violence.” The way to get out of that is to go blind or, like Hedges, to see it and blame others. Hedges doesn’t see himself as retreating “into self-defeating responses, violence, magical thinking and denial.” He’s ringing the bells of doom. Nothing self-defeating or magical about that.

All this brings me back to my muskrat love of Kandiaronk. Who was he? He was a philosopher-statesman of the Wendat Confederacy who was trying to play the English and French off against each other while forming a comprehensive indigenous alliance to stop the settler encroachment. He was described by Europeans as so naturally eloquent that “no one perhaps ever exceeded him in mental capacity.” He was the only man in Canada who was a match for the Governor, who often invited him to dinner and provoked him “to hear his repartees, always animated, full of wit, and generally unanwerable.”

This is what Kandiaronk had to say about money:

I affirm that what you call money is the devil of devils; the tyrant of the French, the source of all evils; the bane of souls and slaughterhouse of the living. To imagine one can live in the country of money and preserve one’s soul is like imagining one could preserve one’s life at the bottom of a lake. Money is the father of luxury, lasciviousness, intrigues, trickery, lies, betrayal, insincerity—all of the world’s worst behavior. Fathers sell their children, husbands their wives, wives betray their husbands, brothers kill each other, friends are false, and all because of money. In the light of all this, tell me that we Wendat are not right in refusing to touch, or so much as to look at silver?

In Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari tells us:

There is no way out of the imagined order. When we break down our prison walls and run toward freedom, we are in fact running into the more spacious exercise yard of a bigger prison.

The Davids reply:

Nowadays, most of us find it increasingly difficult even to picture what an alternative economic or social order would be like. Our distant ancestors seem, by contrast, to have moved regularly back and forth between them. If something did go terribly wrong in human history—and given the current state of the world, it’s hard to deny something did—then perhaps it began to go wrong precisely when people started losing that freedom to imagine and enact other forms of social existence. [502]

It starts with imagining.

For your imagining pleasure and rigor, here is Build a New Model:

Buckminster Fuller said that to change things, you can’t fight the existing reality. You have to build a new model that makes the old model obsolete. This episode outlines ten universal principles of a new model, including the purpose of government, how to measure its success or failure, what community wealth really is, how to protect and proliferate it, the intergenerational transfer of wealth, and paying your debt to society backwards and forwards. I begin by talking about the spiritual and metaphysical obstacles that keep us from imagining a new model and how to remove them in your own psyche. Based on my book, How to Dismantle an Empire, I end with the three powers that communities require in order to control their own labor: debt, tax & cash.

Here is Sex & Power: Battle of the Daves:

David Buss, evolutionary psychologist on mating strategies, claims men are wired to seek multiple partners who are as young and fertile as their social status allows. But why do young women mate with them? To answer that, I consult anthropologist David Graeber and archeologist David Wengrow on the Yanomami of Venezuela, the Mi'kmaq of Nova Scotia, and the Wendats of Canada. They show that sexual liberty was the norm when women owned the economic resources and money was just a plaything used for status, political apologies, and gambling.

and The Economics of Anarchy, to catch up with our past:

Economics is a system of organizing labor by issuing and collecting money backed by ownership of the assets; anarchy is rule by rules rather than by rulers. As the czar or czarina of your fiefdom, what will your policies be? This discusses Universal Basic Income, student debt forgiveness, naive do-gooders, capitalism vs. socialism, and cheap vs. free. As a supplemental economy, it takes the mortgages back from capitalists and takes the social pension back from government. It enables those who work for corporations to benefit from the local economy while adding to the reserves that generate more prosperity. With a segue into a spirituality of enough, it ends with Matt Ehret on protectionism vs. free trade and the need for a standing army.

Interesting. It supports the ideas I put into two mini-courses I put together 20 years ago after being appalled and shocked at how wrong university, hence world, economic practices are. Economics has become our biggest religion because more people on the planet will be allowed to die or be killed for its 'truth'. It is total bullshit. I wrote and taught "Economics Debunked" and "Banks Skanks". Graeber's book fit into my understanding perfectly, and filled in many gaps. Wonderful read.

Thank you for sharing your ideas. And I will get 'muskrat love' to read. We have entered a time when a rebirth of imagination and curiosity is required. We are living the Bhagavad Gita and I am so happy to be fighting with Arjuna. Amazing times we are in.

Thanks Tereza, lovely words and everything, and yes also https://gduperreault.substack.com/ - I extend your comment about imagination and curiosity rebirth: that I sense/believe/witness that this has been happening for a while (perhaps always, given the uncertainties and likely many falsehoods of time/space/light/energies, etc) and Tereza/you/we are (all actually) evidence of this magical flow and transcendence.