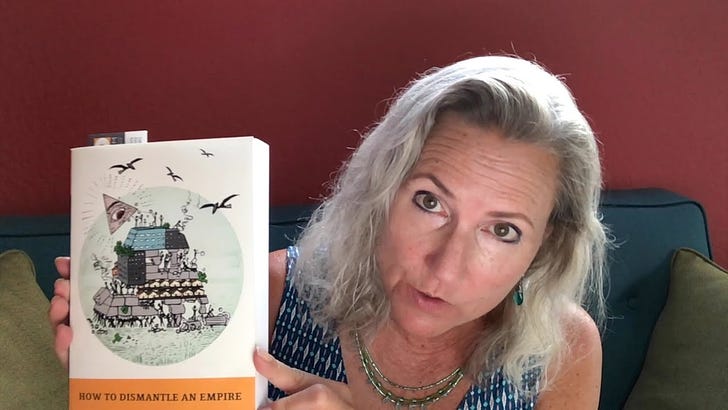

15: I Heart Money

This is Chapter 15 of my book How to Dismantle an Empire. It begins Section FIVE: Lands of Milk and Money. In the first four sections we’ve gone from the ancient past of anthropology to the recent past of the last 500 years, and from financial scams that control countries and their resources to ones that take over cities and populations in the US.

In these last two sections, we move into the future by imagining how we’d want money to work, building on the knowledge of how we’ve been tricked before. This chapter applies the techniques of system change, comparing money to blood in a body and water in an ecosystem.

At the end, I’ve attached the link to Chapter 16: What If Money Was No Object? which I released previously. It continues on the underlying philosophy of money and viewing it as if you’re inventing the concept. So this is a two-fer!

As always, I start with quotes:

This planet has—or rather had—a problem, which was this: most of the people living on it were unhappy for pretty much of the time. Many solutions were suggested for this problem, but most of these were largely concerned with the movements of small green pieces of paper, which is odd because on the whole it wasn’t the small green pieces of paper that were unhappy. —DOUGLAS ADAMS Learn to recognize the counterfeit coins That may buy you just a moment of pleasure, But then drag you for days Like a broken man Behind a farting camel. —HAFIZ

i heart money

We come now to the crux of the problem: how do we transition from a money backed by slavery to a system that supports small-scale sovereignty? For the producer nations, the quality of life would increase with freedom. But consumer nations like the US would be in deep trouble. Our money is now redeemable for products made by people who don’t own their own labor. The goods and food that we buy rents slaves by the hour for a fraction of what our own time is worth. The meager currency they receive is redeemable for products made by people whose time is worth even less than theirs, never from us. No just and sustainable economy can compete with that.

The small green pieces of paper and counterfeit coins are dragging us behind them, with us holding our noses but not knowing how to break free. The reality is that in a fair economy we would have a lot less stuff and do a lot more manual labor. If we were subjected to a fair economy tomorrow, we wouldn't survive. That isn’t a popular platform on which to launch a revolution.

However, perhaps we can assume that the slaveowning economy will fail eventually by virtue of the slaves or by vice of the masters. How to bring it down isn’t our concern. We’re looking to design an alternative system that frees ourselves from the necessity of slaveowning, and perhaps makes some friends on the other side. In a best case scenario, this would all happen gradually while we increase our productive capacity. That's our purpose here.

What functions should money serve in order to support small-scale economies? It should facilitate internal trade, foster local resilience, and focus energy and labor on common projects. It should recirculate within the economy and protect the natural, physical and human wealth of the community as a whole. There should be enough to keep every person gainfully employed but not so much that it raises the cost of living. It should reward honest work with security and the capacity for generosity but prevent monopoly, extraction and overaccumulation.

the body politic

In this section, we'll be practicing systems thinking in order to break out of the habit of thinking like an empire, where money is trade and therefore it's perfectly natural for goods to flow from producers to consumers. To understand how money could operate differently, we'll develop two metaphors of truly natural systems of circulation—blood in a body and water in an ecosystem, starting with blood.

Blood serves to bring energy to whichever part of the body can use it. As the body grows, in childhood or pregnancy, the amount of blood increases with the need. When food requires digestive work to extract energy, there’s no need to convert it to excess fat. Too much blood in fast circulation creates a high-pressure environment but the loss of blood compromises and taxes the whole system. Blood communicates between all the parts of the body, making sure that nothing is wasted and every individual cell is nourished.

Likewise in a community economy, money keeps trade fair and sends energy wherever the health of the social body is fostered. Money recirculates within the community based on participation, while trade with the outside world is in the things that the body produces, not the vital organs of farmland, resources, water, communication systems, or transportation. While government is the mind of the body politic, the economy is the heart; the mind decides what the body should do but the heart sends out the energy to get it done.

Families and neighborhoods are the muscles and limbs that make the good things happen. To promote the things that make the body healthy—wholesome foods, clean fuels, fair industry—money can be as vital and abundant to an economy as oxygen is in the bloodstream. It can grow with the community, so there’s always enough, but not so much that it raises the cost of living and creates a fast-paced, high-pressure lifestyle. It can stay in perpetual circulation without ever bleeding out or getting sluggish with accumulated fat. It can invigorate fresh growth so that youth grow up strong and capable to interact with the world, take care of the elderly, and nurture the next generation.

This isn’t the way we usually think about money, which now feeds the social body the junk food of quick sensation and no nutrition. After getting us hooked into this diabetic spiral, the austerity government asks us which digits we’d like to amputate first. It doesn’t have to be this way. To change how we think about money, let’s continue expanding the metaphor beyond the body and look at money as water in an ecosystem.

money as water

Water in a healthy ecosystem nourishes that which is beneficial for all of the inhabitants. The species that are indigenous to that ecosystem co-create a geography that suits their needs. Life adapts to use whatever is available and thrives in rich or poor soil where what is is always enough. As long as water recirculates in an ecosystem, it doesn't matter whether there's a little or a lot. Since every drop is conserved it's always sufficient and it's always free.

Like water, there are no money shortages, only money leakages. If a lush and verdant biosphere can be located smack dab in the Arizona desert, a self-contained community can flourish, whether wet or dry, rich or poor, urban or rural. Like water, money can grow on trees and fill aquifers that can be drawn on in times of need. Native grasslands can go deep, avoiding artificial irrigation. The natural process pulls water up through green channels and distributes it, giving seedlings and saplings a viable start.

But when water is artificially piped in from outside the area, like money extracted from other places, a thirstier type of plant can flourish. These plants choke out the more frugal succulents and compete between themselves for the increasingly scarce resource. With the ecosystem stuck in a cycle of dependency, water goes into manicured lawns and golf courses, not where it's needed or best used. More and more water becomes a necessity rather than a luxury, just like the need for more and more money—water or money rules the land instead of serving it, creating a need that only it can fulfill.

This thwarts the true purpose of money, which is to circulate and feed the diversity of life attracted to that area, allowing each unique expression to reach its wildest and most elated potential. No community is poor by its nature, only after it’s been made dependent on an outside resource and then deprived of it. Societies where money circulates slowly and sparsely can be as beautiful as the Sonoran desert.

When corporations or even international aid brings a revenue stream to a cash-poor country, it’s not necessarily a boon. It creates deprivation for those who didn’t formerly feel poor because everyone was the same. It would be like a desert mariposa lily suddenly feeling shabby beside a hothouse amazon lily.

The “solution” to deserts and rainforests isn’t a more equal distribution of water, it’s recognizing the uniqueness of each environment. In the same way, the answer to economic disparity isn’t to first centralize and then control the distribution of capital. This would be like damming the rivers and making it illegal to collect rainwater, making everyone dependent on the same irrigation ration. Instead, the solution is to give each community control over its own wealth, which includes its land, water, resources, people, and especially credit creation.

Currently the US government doesn’t even create its own money— it borrows from the Federal Reserve whose private banks loan money into circulation through mortgages to the public. To illustrate the dysfunctionality of debt-generated money, let’s look at what would happen if water were loaned into existence.

more equals less

Imagine that God makes the world an offer it can't refuse: I give you enough water to grow and you repay me 5% in water each year. The plants get busy and do fine for a while. But after four years they go to God and ask to borrow 20% more to replace what they had paid. God obliges and their debt interest becomes 6% of the water remaining to cover the loan. In a little over three years, they again replace the lost 20% and the interest becomes 7%. In a little under three years it goes to 8% and so on. The world has been trapped in a cycle where all life exists only to produce water, which is siphoned off and sold back to them, increasing the debt. Life has become subservient to and controlled by the need for water. There's no escape.

The same dynamic holds true with bank-generated money. When money is borrowed into circulation, there's never enough to repay the loan plus interest. Where would the extra money come from? Like water, that's all there is. It creates a cycle of dependency and control. Instead of flowing out to nurture what's beneficial for the community, it pools exactly where it's least needed and most squandered. Like water, the more there is, the more the inhabitants need because it raises the cost of living. Rather than being a benefit, more equals less self-reliance.

Therefore “financial independence" is a contradiction in terms: money and self-sufficiency have an inverse relationship. The higher the average income, the more difficult it is to go without. In a Oaxacan village, a family with no money may still have a home and food to eat. They may get along just fine. In the US, the more a person makes, the more dependent they are on continuing to make that much or more.

In the US, the flood of foreign-made goods covers up a drought of self-sufficiency. The high cost of living makes it nearly impossible for First World producers to stay afloat—their fixed costs are an anchor around their necks in a market that's awash in cheap, disposable junk. The US is drowning in debt and paraphernalia while the Third World is a credit desert.

In the natural world, water use becomes more efficient as the eco-system matures, with every new generation getting the free benefit of what's come before. No river beaver pays rent for the use of the dam, even though it may not have built it. The new beavers focus on improving the family’s lodge for the arrival of the next kits.

But in the world of bank-generated money, every generation buys their houses anew with thirty to sixty combined years of their labor. Although no banker ever picked up a hammer to build the house, he owns it. He bought it by diluting the money supply and reducing the value of all previously existing money. The sellers will be lucky if the money they got out buys a quarter of the value they put in. And the buyers are left with a debt that consumes their working life and leaves little time or money to raise a family or improve the home. Life has become subservient to the bankers.

home economics

Let’s move our metaphor now from the biology of the body or the hydrology of the ecosystem to the smallest microcosm of social life: the family. By showing how money works in the most self-contained of social groups, we can better understand how a community economy functions and what the risks are.

Imagine a 1920's farm family who trades around a handful of coins for the work they do for each other. The three kids get up and feed the chickens, gather eggs, and milk the cow. They deliver the milk and eggs to the mom, who pays them each a quarter. The dad brings food in from the field and the mom pays him six quarters. The mom prepares three meals a day and the dad and kids pay her a quarter for each. After every meal, one of the kids washes the dishes, for which the mom pays him or her a quarter. In the evening they do their schoolwork, for which the dad pays them each a quarter.

With circulation of the same dozen quarters, the division of labor is kept fair. They can still do favors for each other but the baseline is equal so it makes it obvious if one person is doing all the work and another is shirking. It doesn’t matter whether the medium of exchange is a quarter, a seashell, or a hundred-dollar bill.

In addition the family members sell their extra produce and the honey from their beehives in the market. This money goes into a cookie jar where it’s used to buy things they vote on together—tools and materials to make their work easier, pretty dishes to make the food taste even better, fabric for new clothes, new animals for breeding, exotic spices for cooking, games and books for long winter evenings around the fire. They work hard but they live pretty well.

But let's say that the son loses a quarter gambling on the playground and decides to just skip a meal. With only eleven quarters in circulation, the mother has to cut down her payments for food and give the dad five quarters. He then has to skip a meal himself every day or stop paying the son for homework. The son drops out of school and sleeps through breakfast and morning chores, so he's down to one meal per day and the others have to do his work. By the end of the week, they've entered their own Great Depression. There's the same amount of work to be done and goods to be had as before, but the medium of exchange is diminished. Like the real Great Depression, the extraction of an arbitrary, artificial symbol that could have been replaced with a fancy rock has left them all depleted and vulnerable.

carbs, fuel, tech, & money

Accumulated money tends to emigrate out of the system, as in third world countries where the wealth created by land monopoly goes towards luxury imports. If our hypothetical family had traded in sea-shells rather than quarters, they would only be useful for equalizing labor within the family; there would be no point in hoarding them. Or the family could have made an exchange rate of three seashells for one quarter from the cookie jar, slowing the leakage of money but rewarding those who take on extra work.

To protect a community’s internal trade, two credit systems are needed: a taxed one for imports and a tax-free one that's only good for local exchange. A community currency is like the coins the family trades around—as long as they stay in the family, they’re merely tokens that keep trade fair. Because the services and goods provided within the family are free, they can afford to be as lavish and generous as they want. Whatever they give is essentially given to themselves.

The difference might be described as fast money, which can rocket around the globe in seconds, and slow money, which saunters between neighborhoods. In many aspects of modern life, faster is not always better: highly processed carbohydrates give a quick burst of energy that hasn’t been earned by the body. They simulate happiness by producing endorphins while the body is essentially passive. They are partly predigested so they hit the bloodstream instantly without needing to expend energy to break them down and release them slowly.

While these fast starches are the fossil fuels of the body, fossil fuels are the sugar of society. Without producing its own energy, society gets the results of effortless transportation, heat, light and entertainment. Likewise, food is hypergenerated through petrochemical stimulation of the soil, only to leave it more depleted when the sugar high is over.

In similar fashion, fast technology overstimulates the brain, giving it the false sensation of thinking. It’s a pre-processed barrage of information, opinions, humor, and entertainment. It provides an artificial friends-group of screen celebrities without the work of forming and maintaining reciprocal relationships.

Junk food, junk fuel and junk tech are empty calories devoid of any nutritional content. They deliver the thrill of getting something for nothing. Junk money is concentrated trade power, in which the work of producing something for actual trade isn’t done. It may provide the quick hit of a buyer’s high but it has no power to sustain.

perseverance, kansas

However dollars, designed for advantage, can still be used for equality. We'll end with an imaginary example of how a community diverted their excess dollars into a revenue stream for global good.

Perseverance, Kansas, owned the only bank that was authorized to issue credit for local mortgages. With the income from mortgage payments the government wasn’t overly dependent on taxes for city services. This enabled them to give tax incentives to things that were beneficial—not just for their city, but for the rest of the world.

They decided that the most good their money could do was buy back lives in the places where life was cheap. Therefore they designed their tax system to funnel money to global charities.

This is how it worked:

Matilda is a renowned Perseverance potter. She decides to give a workshop to benefit a seed bank in Palestine. A likeminded ceramics studio lets her use their facility for free. Ten pottery students enroll, each writing a check for $30 made out to the West Bank Seed Bank. Together they make some nifty pots and take them home.

Matilda takes the checks to a student group at her neighborhood middle school. They write her a receipt for $300 and give her six Fair Trade Tens. These are certificates printed on banana fiber paper and hand-colored by the students. Each one says, “This $10 in exchange value represents $50 that has been donated to the West Bank Seed Bank.” The students sign them as the issuing treasurer/artist.

The students mail the checks to the Seed Bank, which sends the individual pottery students receipts that they can deduct from their income tax, and keeps them informed on the good things their money has done. Matilda gives the ceramics lounge the $300 receipt from the student group, which they can deduct from their property tax. Finally, Matilda can spend her $60 of Fair Trade Tens at the farmer’s market or any local business, where they will circulate again and again with no sales or income tax. As an extra thank-you, supportive farmers and vendors often give her an added discount to support the cause.

So, for the $300 in charity generated by the community, everyone involved has gotten a tax-free or deductible thank-you and $60 will stay in circulation supporting self-reliance. Multinational corporations will have $300 less and Palestinian seed-savers will have $300 more. A dozen people have, in a small way, turned the tide with the support of their whole community. It’s a win-win-win-win-win instead of a lose- lose-lose for people, communities, and the planet.

CHAPTER 15 EXERCISES

Using examples from the book, or from your own research, logic, and experience, comment on the following and what it means today:

Paradigm Shift #15

Money is a fluid medium that's a conduit for energy. It either moves energy in and down within a community or out and up to serve the hierarchy.

To reimagine money requires looking at what it really does, not what it says it does, and then deciding what you want it to do.

LEXICON

Explain how the following definitions change the dialogue around social problems. Is this concept used in discussion of the examples to which it applies? If not, how does this affect the potential solutions?

slaveowning global economy: a pyramidal organization in which the labor and resources of the world serve the citizens of the developed countries, whose citizens then serve the interests of the rich.

extractive economy: use of community capital (natural, physical or human) that diminishes the community's wealth (capacity for self-reliance) while enriching individuals inside or outside the community with the ability to control other people's labor (money).

regenerative economy: use of community capital (natural, physical or human) that increases the community's wealth (capacity for self-reliance) while distributing individual wealth (capacity for choice in self-reliance) as widely as possible.

small-scale sovereign economy: a horizontal network in which the smallest number of people practical for that function control their own wealth (capacity for self-reliance) by owning their capital (natural, physical and human) and their labor (credit creation and taxation).

fast money (or carbs, tech, or fuels): a highly refined extractive process that delivers a burst of energy without requiring the body (physical or social) to do any work to produce it. Operates to the long-term detriment of both the producer (nature or people) and the recipient.

QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION AND DISCUSSION

Is it too strong to say that the First World, including its minority citizens, are a slaveowning economy? Would "slave-renting" be more accurate, or does it dilute the word slavery to use it for anything other than the chattel form of physical capture and bondage? How would you otherwise describe those whose labor serves others' interests with no reciprocity to their entire country or to the global producer class?

Extend one of the metaphors in the chapter or design your own metaphor for money. Are there other things that are too fast in our society? Would or could a small-scale economy slow them down? What's the impact of an extractive economy on family? Could you imagine this being different in a small-scale economy?

From my book, How to Dismantle an Empire, I read Chapter 16 'What If Money Was No Object?' I compare the eco-nomos to the eco-logos, show a puzzled space alien who doesn't grok money, compare to neo-feudalism, and ask about money's cosmovision.

The purpose of money is to steal our time. The bankers usurp ownership of the properties and issue debt against them, for which we pay with our lives. It's not interest that's usury, it's usurping the right to issue the money. Banks and corporations are seen as heroes because they give us money, government as parasites because they take it—but it's actually the exact opposite. We're subject to a geistheist, the stealing of our spirit, our soul, our purpose. That's what we have to change.

People are inherently good and, when they behave badly, systems and stories are to blame. But which came first? A reader called Winston Smith cites Richard Vobes on 'You are the king!' who refutes taxation. I look at taxation as chump change compared to the mortgage, that makes us servants to the rich. The story of good vs. evil, heirs vs. slaves, is the foundation for the system that backs our money.

Great piece. I love the water/blood circulation analogies!

If we live on Planet Water and if water is “feminine” (moon, menstrual cycles, ocean), then we have done so much canalising of water - draining super productive wetland ecosystems, channelising streams, concreting river banks, “reclaiming” land from ocean (not that we ever claimed it), flood/river engineering projects, dams - the masculine command-and-control authoritarian approach.

And I was randomly thinking about a Venetian/Phoenician comment you posted somewhere and how Venice is so canalised…What we do to water, we do to money. What we do to women, we do to the economy

My copy of this book arrives tomorrow. I will be listening to the playlist along with reading it. You break down the concepts of money and economics into a digestible format. I’m excited to learn better how it all works.

Question: as the stranglehold that money has on a society increases, we tend to overextend ourselves more and want more. Why? For example in the 50’s when one income was enough, families lived more modestly in smaller homes with fewer expenses. Today our money is worth so much less but we want/“need” so much more.

It’s nice to have all these luxuries today but why is it a collective mentality to always overspend and then be a debt slave? Are we all that brainwashed by consumerism?